Hospitals are increasingly giving patients and families opportunities to explore, play, and socialize during a hospital stay. Many facilities offer communal spaces like lounges, playrooms, and healing gardens. But what happens when a patient is unable to leave their hospital room?

Over the past several months of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has felt like the entire world is under isolation. We have all faced challenges to our freedom to socialize, explore, and play. As society is adapting to these new constraints, so too are hospitals. To keep patients, families, and staff safe, healthcare facilities are using widespread and stringent isolation precautions more than ever.

SHORT-TERM SOLUTIONS

Healthcare workers have been forced to rapidly rethink how they use their facilities to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Family lounges and playrooms provide important support for emotional well-being, but, like any communal space, they pose special safety challenges during viral outbreaks. In the short term, facilities are frequently making the difficult decision to close or limit the use of these resources. In a recent survey released in June by the Association of Child Life Professionals, a massive 76% of the 721 respondents across the United States reported a temporary closure of their facility’s playrooms in response to the pandemic. [1]

Above: Metcalfe keeps safety and infection prevention in mind when designing for any healthcare space. These interactives, located throughout the lobby and waiting areas of a pediatric ambulatory care center, are activated by motion sensors instead of buttons or gears. This discourages the transmission of germs from contact with potentially contaminated surfaces.

COVID-19 IS NOVEL, BUT ISOLATION REQUIREMENTS ARE NOT

It is important to remember that patients have been under isolation before the pandemic – and there will continue to be reasons for such restrictions after it. Isolation requirements are by no means new. Patients can be confined to their room for a variety of reasons, like a comprcomised immune system, limited mobility or severe fatigue. Healthcare facilities must address a patient’s needs for socialization, play, and exploration – even if those patients cannot leave their room. Their isolation comes at a time when stress is elevated and social support is of the utmost importance.

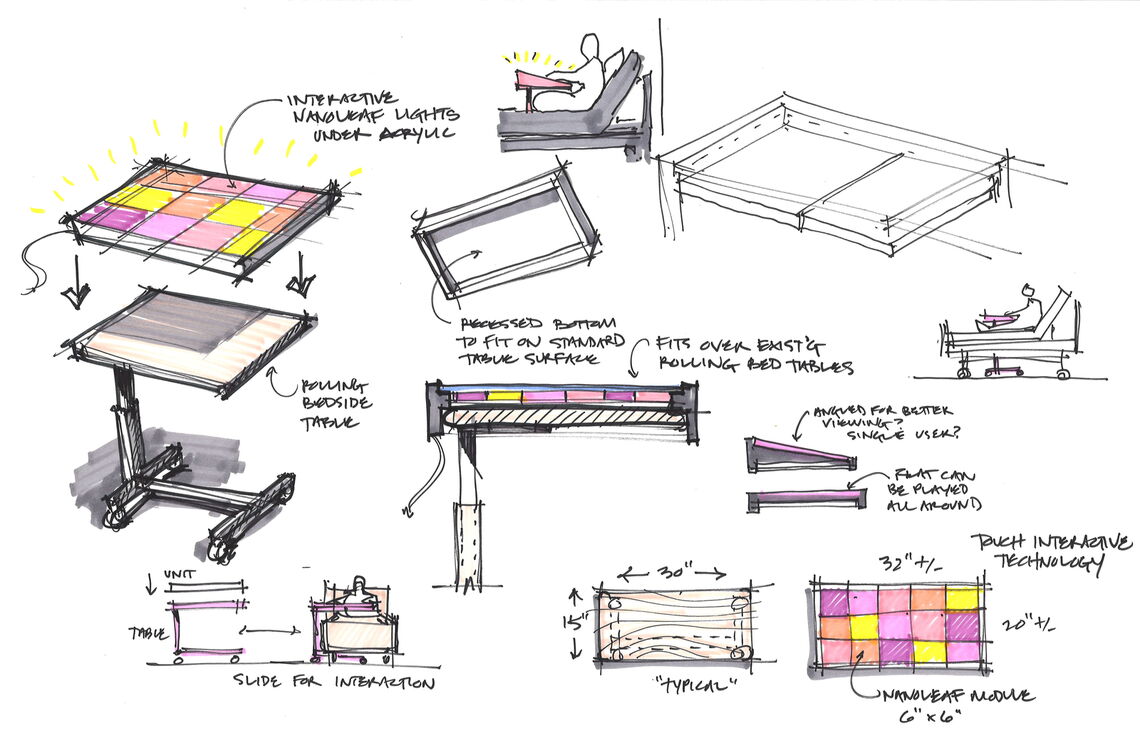

Above: Metcalfe is exploring ways of adapting engaging elements normally found in communal spaces for use at the patient's bedside. Our sketches above explore how we could adapt an interactive LED light wall we recently designed for Lancaster General Hospital to function atop a patient’s bedside table.

Metcalfe works with hospitals to create richly engaging, interactive play environments. We are combining lessons learned from this pandemic with earlier research, like Rodger S. Ulrich, Ph.D., EDAC, an expert in evidence-based healthcare design, to improve emotional support for isolated patients. We know from Dr. Ulrich’s work that the following three factors are the main influencers of a patient’s level of stress caused by the built environment.

- A sense of control with respect to physical-social surroundings

- Access to social support

- Access to positive distractions in physical surroundings [2]

To address the stressors caused by isolation, we help our clients explore ways of bringing experiences normally found in playrooms to the bedside. Play allows patients to have a sense of agency and control over their environment at a time when they have control over little else.

Just as healthcare designers can meet an isolation patient’s infection control needs by planning for the control of air pressure in a room or adding an anteroom, designers should consider this patient type's unique psycho-social needs. Their isolation puts them at a significant disadvantage for addressing the factors Dr. Ulrich’s work identified as the main influences on a patient’s stress level.

PLANNING AHEAD MAKES ALL THE DIFFERENCE

We recently collaborated recently with the team at Stantec to develop interactive play elements throughout a new pediatric inpatient unit they designed for Lancaster General Hospital (LGH). The entire project team was willing to push the boundaries of what a “playroom” should be. Along with a digital design team, Night Kitchen Interactive, we designed a gigantic touchscreen “seek-and-find” to entertain patients and families during their stay. Even in the early stages of planning, we recognized that we could adapt this play feature to also function at the bedside. The hospital had planned to place iPads in each room, so we created an analogous version to work on these tablets.

Above: Metcalfe and Night Kitchen Interactive developed a digital “seek-and-find” at Lancaster General Hospital that is scalable and adaptable to either a communal playroom setting or an isolated bedside.

We also encourage hospitals, like Lancaster General, to distribute interactive elements throughout the unit – instead of just inside a playroom. By working together with Stantec and the hospital, we strategically kept two interactive elements within the central playroom but then distributed two throughout the corridors of the unit. Michelle Arnts, BA, CCLS, a Child Life Specialist at LGH, noted that “vicarious play” has become an important method of interacting with patients during this pandemic. [3] Through this technique, the care team engages patients by playing “for” them. The patient provides direction and cues, and a member of the care team acts on their behalf. By distributing the interactive elements throughout the corridors, we provide a greater likelihood that patients can view them from their window and play with them vicariously with staff assistance.

Above: These automata (animatronic figures) are located toward the back of the inpatient unit at LGH. They are placed strategically to be viewable from the windows of patients who do not have a view of the other play elements at the front of the unit. This way, if patients are unable to leave their room, staff can help them play vicariously. Patients can ask staff to push buttons for them to animate scenes within the automata.

Play cannot happen unless there is agency on the player's part – even if the player must play vicariously. In a situation where the player is isolated, Metcalfe’s complex understanding of play helps hospitals identify and develop ways to establish that sense of agency and keep the patient engaged.

We know how difficult it has been for everyone to cope with the added degree of isolation the pandemic has caused. It often feels like we have little control over anything right now. We must counteract this by thoughtfully – and safely – supporting our basic human needs for socialization and play.

ENDNOTES

[1] “COVID-19 Child Life Staffing and Programming Changes: Data Collection Window June 1-8, 2020.” Association of Child Life Professionals, 15 June 2020, www.childlife.org/docs/default-source/covid-19/covid-19-child-life-staffing-and-programming-changes-june-1-8.pdf.

[2] Ulrich, Roger S. “Effects of Interior Design on Wellness: Theory and Recent Scientific Research.” Journal of Health Care Interior Design: Proceedings from the ... Annual National Symposium on Health Care Interior Design. National Symposium on Health Care Interior Design, Feb. 1991, pp. 97–109.

[3] Freilich, Hayley T. “Interview with Michelle Arnts, BA, CCLS.” 2 June 2020.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Hayley Freilich, PMP, EDAC, is the Director of Healthcare and Patient Experience at Metcalfe. She is a passionate supporter of patient and family care and works to enhance how patients, families, and staff experience their healthcare journey. For more information about Metcalfe’s work in healthcare, please click here or contact Hayley directly at hayleyf@metarchdesign.com.